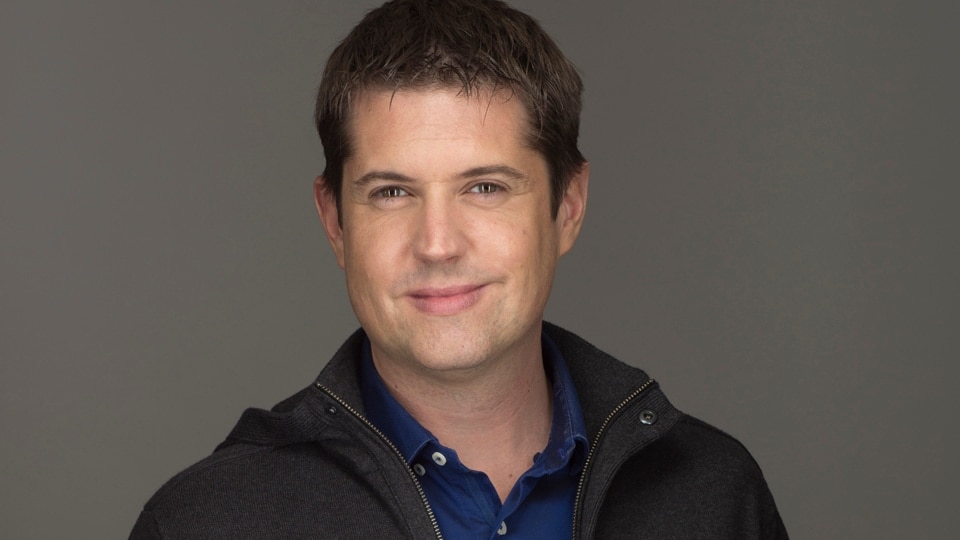

As Executive Vice President of Creative for Ubisoft's Canadian studios, Lionel Raynaud has a hand in overseeing, shaping, and guiding the development of some of Ubisoft's biggest franchises, including Assassin's Creed, Far Cry, and Rainbow Six Siege. During Ubisoft's pre-E3 corporate event, he spoke about how Ubisoft's design strategy is shifting to face the future, with games and worlds increasingly being used as platforms to continually tell new stories, all while giving players greater freedom to do whatever interests them. Following his talk, we had a chance to speak with Raynaud about Ubisoft's changing priorities, advances in technology, and how players are increasingly taking control of game narratives.

Ubisoft has a long history, but there was clearly a moment when things changed, and things were set in motion to make our open-world games what they are today. What made that lightbulb go off?

Lionel Raynaud: I guess the special point in our history was the release of Assassin's Creed, because it was our first take on open worlds, and we were kind of defining an action-adventure game with this kind of technology and a new navmesh system that allowed us to have parkour. Very smooth navigation through an open world, the beginning of social stealth, all these things are together. They kind of defined the genre. And we all witnessed that from the inside, but still it created this energy that, yes, we can define a genre that other publishers will envy and will want to follow, and this has defined the culture.

Creatively, how does Ubisoft decide how long to keep creating new content for a live game after launch, as opposed to moving on to a sequel? Where does that line get drawn?

LR: This line gets fuzzier every year. We have bigger post-launch periods, longer lives for each of our games. Even the ones that used to be solo-oriented games, like action adventures, they now have a very strong post-launch, and people are staying in our worlds for a long time. So this line is absolutely fuzzier and fuzzier. We all see a future where a game will stay {post-launch], and new experiences will come in the games. But we will have technology that will break the [current] limits of memory, for instance, because of new technologies that are arriving. We would be able to – in the same world – have several historical periods, for instance, in Assassin's Creed, and use the Animus to travel from one to the other. Or have different areas of the world linked by travel systems, so that a Far Cry game or a Watch Dogs game could happen in different countries in the same experience, seamlessly.

You've spoken about how Ubisoft games have recently shifted from presenting one long narrative to a lot of smaller, self-contained narratives that fit into larger story arcs. What drove that shift, and how has it changed how players engage with the games?

LR: What drove this is the will to not give finite experiences. The idea was that you have this conflict, and the resolution, and then it's finished – you've killed the bad guy, for instance. We build a strong nemesis, and the goal of the game is to kill him or free the country, we've done that a few times in our games. But when you succeed, you have to leave the game, because there is nothing else to do. So the goal was to break this, and say that you will be the hero of a region or population many times, not just once. And if you get rid of a dictator or an oppressor, something else is going to happen in the world, and you will have a new goal.

This is why I talk about having several fantasies; not only being the hero who's going to free a region, but maybe also the fantasy of having an economic impact, of being the best at business in this freed country, or even having a say in how it should be governed, now that you've gotten rid of the dictator. And I think we can have several different experiences with different game systems in the same world, if the world is rich enough and the systems are robust enough.

How is the advancement of AI freeing up more creativity with our teams?

LR: It has so many applications that we are only seeing the beginning of it at the moment. We have started to work on [developer] pipelines – how to accelerate pipelines, and create content faster, so we can have more content. We are already doing this in the Canadian studios.

AI will also have an impact on NPCs and the way they behave. This is a complicated thing, because it's not only a question of the power of artificial intelligence; it's also linked with the rules of game design that make the experience interesting. A good example of that is with stealth; you don't want AIs to always be amazing at stealth and stab you in the back. You want to have a system that players can grasp and want to play with. It's more of a toy than a super-AI that is going to kill you no matter what you do.

The direction AI is headed in that's going to be interesting is how human characters feel when you talk about them. Can they keep a strong memory of what happened in the game? The first take on that was Far Cry 5; because of the open regions and the fact that players could do whatever they want, we needed to have NPCs react to what happened in other regions. So when you cross into Faith's region, for instance, even if you've just arrived, some people will know you because you did something amazing in another region, and they will comment on that, and say ‘thanks for what you're doing, it means something to us, and we are with you.' It takes us back to relatedness, creative links, feeling that we're important to [these characters]. And with AI, we have a long way to go, obviously, to have these characters feel more human. But we now have the technology that will allow us to go there.

You've brought up "relatedness" several times as a core part of self-determination theory. Can you talk a little more about what that means in the context of games?

LR: For us, it's the need to belong, and the feeling that you are part of a community, and that others are important to you, and you are important to them. These tools allow us to make design choices on different scales.

On the macro scale, it's exactly the way we design Operators in Rainbow Six Siege, or Heroes in For Honor. We design these classes so that you are happy to have another player with a different class, so that you can play with greater synergy and become more efficient. The whole meta of Rainbow Six is based on that. Every time you bring a new Operator to the roster, it creates a new strategy. It allows players to say "all right, I will play as this guy because I'm used to playing with these friends, and I will support them, or I will tank, or I will be the one who creates the line of fire, because I have these new abilities." And players will talk about the ways they're going to play these combinations of Operators before they're even in the game, and this creates very strong relatedness.

On the lower level, almost micro, when you use XP boosts in Rainbow Six, other players will benefit from them; even if you're the one consuming it, they will have a small percentage of boost as well. So in a way, even if you're not a super-good player, you're already useful to your team and other players. They are happy that you're here. Sometimes we review existing systems and features, and we just ask ourselves, "Can we make a difference in autonomy, relatedness, or competence by tuning something or adding a small detail to it?"

Almost like building community using just the mechanics of the game.

LR: Exactly. And when we make games that open content to users, we are also boosting that, because we are creating a new community of game makers inside the game. That's what happened with Far Cry Arcade. We've had user-generated content for a long time with Far Cry, it's kind of legacy, but we are opening that to more games.

With The Division 2, we're seeing an example of a game made by studying the habits of players in the first game, and appealing to what they liked best. How does building a game with player feedback and open-world freedom in mind affect the storytelling?

LR: So we have data, and what we call heat maps, [which offer] strong knowledge of what is played and replayed, so we can have a good insight on what is interesting for them. The other way to see it is, especially when we create a world with the possibility of many different stories, is to have very different tastes of stories, depending on the characters. If we have 500 characters in the game we create, we can decide which sections of characters will appeal to a certain audience. There were questions about romance [during the corporate event], and it's very obvious that there is an audience that is waiting for this. And some of our games are really ready to offer not only gunplay and fights, but romance, or friendship, or a ton of other things that would be super-interesting – and make the characters become more interesting and lovable because they don't speak only about fights, but also about things that players live in their own lives.