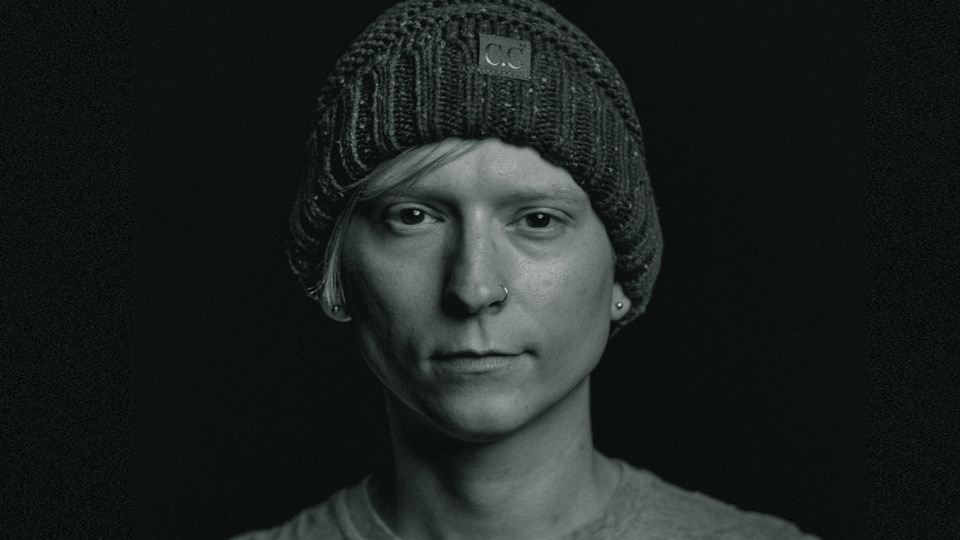

Taylor Epperly's journey into game development began the moment her father returned home from work with modded WAD files on floppy disks for Doom II: Hell On Earth. Seeing how her father's coworkers could transform and modify the game made her realize that people make games, and that one day, she could too.

Epperly's passion for videogames led her to a job at GameStop, where she was able to meet other eager peers looking to break into the industry. Through her connections made at GameStop, Epperly was able to secure a job as a tester at a nearby Ubisoft studio, Red Storm Entertainment. After helping test multiple titles, she transitioned to game design, and has since worked on Ghost Recon: Future Soldier, Far Cry 4, and The Division. Today, Epperly is a senior game designer working on The Division 2.

Did you start working at GameStop hoping it would be a stepping-stone into videogame development?

Taylor Epperly: Not really. I just knew that I loved games and wanted to be around them. At the time, I was going to community college and working towards a degree in programming, but I actually dropped out to become a tester. I don't recommend anyone do that, but it happened to work out for me. I worked as a tester for about two years before also working as a receptionist, which helped me get a lot of face time around the company. Soon after that, I applied for the game designer position and was hired.

What experience had you had designing games at that point?

TE: I used to write mock design documents when I was young about the changes I would make to a game. In the late ‘90s, I was exposed to the modding scene, and I really enjoyed going into a game and tweaking the weapons, or giving myself 1,000 rounds of ammo and making each shot do a billion damage. Funnily enough, that's kind of the stuff I ended up working on in my career.

Testing itself gives you a lot of experience in-engine as well. We would use the engine tools to document bugs, so I knew my way around the engine. When they were looking for someone to take over some scripting stuff, it made sense to give it someone who already knew the tools.

"Game designer" feels like it could apply to a lot of different roles. What exactly do you do as a senior game designer?

TE: I am a systems designer, which falls under the umbrella of the "game designer" role. I design systems and implement them in-game. One of the systems I worked on in The Division 2 was Rogue, and everything that goes into being Rogue. For example, what happens to the rules once you decide to kill someone in the Dark Zone? What are the rewards or consequences for going Rogue? I work in a lot of Excel sheets, pretty much everything I do starts in Excel. Once the system is in the game, I spend a lot of my time tweaking numbers and values to try and make a good player experience.

What about designing systems appeals to you?

TE: I like fiddling with numbers and seeing what happens. That's what I did as a modder. I like playing with things and trying to break them. That's one side of the game design coin; you need to be able to break things, and in the process of breaking them, you figure out why they're fun and how to make them more enjoyable. That's my favorite part: getting in there and pushing a system to its limits.

How do you know when a system is working right?

TE: It entirely depends on creative direction. We get together with the creative director to define the core pillars of individual features and say, "We're shooting for this experience, but what we're actually getting is different." We then have the conversation of how can we make this fit into our core pillars. Sometimes, it means adjusting the pillars themselves, because maybe you've found something more fun than what was originally planned. You only really find those things out by playtesting and gathering data.

As a systems designer, I love getting data on the precise metrics of what players are doing when they're playing and interacting with my systems. That information is vital to me when we're finalizing and fine-tuning systems. Sometimes, we as designers sit down and have specifically focused playtests where our goal is to break something. We try to push something to its limits and see if we can exploit it. That's where having a background in testing is so helpful.

In many ways, Red Storm helped pioneer the tactical shooter genre. What is it like working for a developer that's been so prolific in the genre?

TE: My dad was, and still is, a huge Tom Clancy fan. I grew up with shelves lined with Clancy books. Coming into work and seeing the name "Tom Clancy" everywhere is a little surreal. The special attention that Red Storm pays to things like gear authenticity really shows in our games, even today.

I never played a ton of the original Rainbow Six, but I still remember playing Ghost Recon for the first time. It was such a different experience from anything else I had played up until that point, so it's been amazing to have been able to work on a Ghost Recon game.

You work primarily in systems, but you've also helped design some features that allow players to dramatically customize the UI. How did that happen, and what were you trying to achieve?

TE: It was a bit of a unique case, because the ability to customize the UI existed in the previous game, but it was pretty limited and not very accessible. My goal was to make it very accessible, so that everyone could use it and immediately tell what impact their changes would have. The only way that I saw to go about that was to create an entirely new UI for it. It's completely new territory for me.

When we start out on a project, our team leaders dole out responsibilities, and we're allowed to say what our preferences are. That's how I was able to work on Rogue systems this time around. Meanwhile, there were some support features that were up for grabs. Customizing the HUD was a task that I took on because I felt strongly about it.

Why did you feel strongly about it?

TE: I think accessibility in videogames is something that's really important to me. I'm always looking at what other games do in terms of accessibility, just to see what players are looking for and what I don't know that players need. For example, in The Division 2, we have text-to-speech and speech-to-text options, and before I had heard about the Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA), I had never even considered the need for those types of tools in terms of accessibility. It was a blind spot for me.

I've lived the life of being the outsider before. I've experienced what it's like when even the people who make something say it's not for me. A lot of games don't really address gender or gender options, so when games do offer those options, it's really meaningful. If you look at some of the more recent Far Cry games, you're selecting your body type, not a gender. Those types of things instantly resonate with me. Some games even go further and let your choose a pronoun. Other games let you change things about your identity after the fact, because games reflect reality, and in reality you can change things; I've changed things. South Park: The Fractured But Whole even does that in kind of a joke-y way, which I appreciate.

Do you feel like videogames are doing a better job of representing the people playing them?

TE: Absolutely. I think there's been a bit of an uproar when games don't do at least the bare minimum. Games get called out in those situations for not doing enough. There's kind of that social pressure, which I think is a good thing.

Have you ever had an experience in a videogame that you felt was for you or was representing you?

TE: The most recent BattleTech game had some really great pronoun options in their character-creation setup. If you had told me, even just five years ago, that there would be pronoun options in a game about mechs blowing each other up, I probably wouldn't have believed you.

Also, there are some obvious gaps in their roster, but Overwatch has been consistently inspiring to me with their varied representation of women. I got into Overwatch late because no one told me there was a pink-haired Russian weightlifter lady in it.

What actions do you think Ubisoft is taking to increase diversity and inclusion?

TE: A couple of weeks ago, a bunch of us went to Montreal for diversity and inclusivity training. I was asked by the HR team here at Red Storm to be an inclusion ambassador for the studio. The people that were selected went to Montreal and got some hands-on training. The training was making the case for why diversity and inclusion is important, not just to Ubisoft, but to gamers as well. The more diverse and inclusive we are, the broader the audience we can reach. I'm now a facilitator for these types of discussions, and we make presentations to our teams and studios for why diversity and inclusion are so important.

Why do you think you were asked to be the ambassador for Red Storm?

TE: I think my identity and background was part of the reason. I think I bring a unique perspective to the conversation, and I'm pretty vocal about diversity and inclusion, both internally and externally. I'm not shy about it on social media, so I think it made a lot of sense for me to be the ambassador.

What can game studios do to be more inclusive?

TE: It's important not to just rely on the normal pool of candidates. I think that if you're not seeing a certain community represented than you should put in the effort and take the extra step to reach out to underrepresented communities. Yeah, it's more work, but the payoff is self-evident.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to do what you do?

TE: Make stuff. Make mods, learn Unity or Unreal Engine 4 and make stuff. When I'm looking at the resume of someone trying to get into the industry, I'm looking at the things they've done and completed in the past. Those things are signifiers that someone knows how to produce something finished. It's so much easier now than it's ever been. Anyone can just hop onto YouTube, watch a tutorial, and know how to rig something in an editor. It used to be something that was locked behind experience and books, but now it's more accessible than ever.